Evidence Based Practice

In the pre-hospital environment, evidence based practice (EBP) is about identifying the best available evidence and applying clinical expertise to interpret it. Simply performing clinical practice in the same way as you always did may not result in the optimum care for your patients every time.

Every five years, for example, the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) reviews evidence in the field of resuscitation and publish resuscitation guidelines which are adopted throughout the world by national resuscitation committees. This evidence has resulted in changes down through the years i.e. from 5:1 to 15:2 and now 30:2 compression ventilation ratios. As new evidence is identified there is a corresponding increase in survival from cardiac arrest thus validating the evidence.

PHECCs Medical Advisory Committee (MAC) base their decisions on available evidence when developing Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). A recent example of this is the updating of the spinal injury management CPGs and the publication of the PHECC pre-hospital spinal injury management position paper.

“Evidence-based medicine is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values”, (Stackett, 1996) and is greeted with enthusiasm from some quarters but also has its detractors. Criticism has ranged from EBP being a dangerous innovation perpetrated by academics to suppression of clinical freedom. This suppression is sometimes referred to as cook-book medicine.

Demand for evidence based practice also comes from better informed patients following consultation with ‘Dr Google’ and other internet sources.

The best available clinical evidence refers to clinically relevant research, sometimes from the basic sciences but more importantly from patient centred clinical research into the efficacy and safety of clinical interventions. Clinical evidence may invalidate previously accepted treatments and replace them with new ones that are more efficacious and safer. For example, active pre-hospital cooling after cardiac arrest has been removed from the 2017 CPGs based on clinical evidence. Thus, EBP means constant change in order to bring the best practice to the patient.

PHECC practitioners, in their practice, use both clinical experience and the best available evidence by way of the CPGs, to remain competent. Both are synergistic but individually they are not adequate to ensure best practice.

Figure 1

Without clinical experience, practice risks becoming undermined by evidence, for even excellent evidence may be inapplicable to a specific patient presentation. On the other hand, without current best evidence, practice risks becoming rapidly out of date, to the detriment of patient outcome.

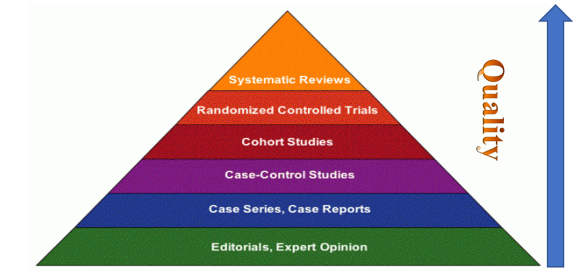

Evidence has a hierarchy where ‘expert opinion’ is the lowest level of evidence and ‘systematic reviews’ are the highest with several layers in between. See

Figure 1. For too long expert opinion was elevated beyond justifiable credit, particularly in the pre-hospital environment. EBP is not restricted to randomised trials and meta-analyses, it involves identifying the best available evidence to answer the clinical questions. If no randomised trial has been carried out for the specific patient clinical event, then the next best level of evidence should be used.

In summary, EBP:

- underpins your clinical decision making

- enables you to quantify benefits to your patients

- provides better assessment reasoning

- enables understanding of benefits versus harm and

- allows you to practice more safely.

Reference

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71-2.